While on an excursion on my weekend off from doing an archaeological survey in Ohio, I decided to venture next door into Pennsylvania and continue my hunting down of magical springs around the world. This expedition brought me to Frankfurt Mineral Springs, nestled in Raccoon Creek State Park in Beaver County, Pennsylvania. It is one of Pennsylvania’s largest state parks. I first stepped into the park office. The ranger on duty told me, “The waters are said to have curing properties, but I wouldn’t drink from it. I don’t think it’s safe.”~ by Thomas Baurley

Frankfort Mineral Springs

Frankfort Springs

Raccoon Creek State Park

Route 18, Beaver County, Pennsylvania

40.497843, -80.427756

In the middle of the park, just down the road about a quarter-mile on Route 18 from the park office, with its own lot, is the ruins of an old mineral springs resort, waterfall, and spring. Back in the day, it was known as the Frankfort House Hotel and Resort. Today, it is a mile-long loop trail following the banks of the creek, during the spring, dotted with white and purple trilliums amongst other wildflowers to the upper end of a wooded ravine within a u-shaped shale and sandstone grotto formation.

Run Time: 5 min, 30 sec.

Soundtrack: Peaks and Valleys by Sean Yukon.

Day on Magisto, Youtube, or Vimeo.

The springs flow down an iron red/orange wall along the entrance to an alcove/cave/rock shelter to the right of the waterfall that flows down from the cave’s ceiling, continuing its journey into the creek. This geologic flow has been operating for thousands of years. It has an otherworldly appeal, tranquility, and magic, a plus for the spiritual and the photographer. The waterfall plunges approximately 8-10 feet through its stone chute. The springs sit at 1,300 feet above sea level and produce approximately 500-600 gallons of water each hour at a constant rate of 58 degrees Fahrenheit. The average temperature of the grotto is 65 degrees Fahrenheit. The spring has a high iron content that stains the walls. Many do drink the water, but the park recommends against it, as it is not monitored for safety.

Composition and Source

The waters of the stream and those of the spring come from different sources – the stream from surface drainage and the spring from an underground reservoir. Therefore, during various times of the year, the stream/waterfall may be dry while the spring will still flow. Seven separate springs originally flowed through the grotto – the original flowed at a 500-600 gallons per hour rate but has since slowed. As commercial development was done in the area, holes drilled into the rock face allowed the water to flow at a uniform rate for bottling. Chemical analysis in 1899 indicated 15 different mineral combinations; most detectable today are sulfur and iron. Guests primarily drank the waters, it is unknown whether patrons bathed in it though that was commonplace for spas like this at that time. The resort used various methods to catch the water, ranging from spring and pump houses to troughs, catch basins, and various pipe constructions.

Advertisement: “The Frankfort Mineral Springs Water is recommended by many prominent Physicians of the State as an aid in the elimination of ailments of the kidneys, stomach, and nervous systems. The water has a special action on the blood, helping to eliminate all the impurities and thus help you to build up a strong vigorous, and healthy body.”

While they bottled up the water and sold it, it was limited in distribution to the resort and local towns, chiefly as drinking water. The resort pumped the water from the springs to the guest cottage, which served as a bottling factory. The water was then filtered by allowing it to flow through layers of white filter paper to remove any impurities, which were most likely the minerals the springs were famous for. They then bottled the water in gallon jugs, five jugs to a case, and sold it even as battery water for early autos.

An 1899 analysis by E.H. Elliot, a former hotel manager, claimed in one gallon of water:

Solids: Grains:

Iron Sulfite 0.43

Iron Chloride 1.55

Calcium Carbonate 3.33

Calcium Sulfate 1.08

Calcium Chloride 1.99

Magnesium Sulfate 0.60

Magnesium Chloride 1.09

Magnesium Carbonate 1.04

Sodium Carbonate 2.07

Sodium Chloride 1.42

Sodium Sulfate 1.00

Potassium Carbonate 0.04

Potassium Chloride 0.57

Potassium Sulfate 0.25

Silica 0.83

Organic Matter 0.88

TOTAL 18.53

No known present-day studies could be found.

Very little is left of the resort; some stone ruins lie atop the stairs winding up to the top of the falls.

History

Before Euro-American settlers, the area was populous with white-tailed deer, elk, and woodland bison with seldom cougars as well as wolves; streams teeming with mink, fox, beaver, and fish. White pine, oak, and hemlock were notable in the area. It was recorded that in the 1700s, the Shawnee were inhabiting the local Ohio River with villages along the banks. By the mid-1700s, the Delaware and Lenape were pushed into what is now western Pennsylvania by settlers in the expanding East. Where PA 168 now resides was once an American Indian trail that follows the western boundaries of the now current Raccoon State Park, very close to the mineral springs. It is believed that travelers along this route may have known of this spring and drank from its waters.

As the French and English explored the Ohio Valley, rivalries exploded between the indigenous and the settlers. The French declared that any river explorer was entitled to all lands watered by its tributaries. The English insisted that the various independent tribes owned the lands. The English had alliances with the first peoples and gave them the protection of the British Crown. The rivalries sparked the French and Indian War from 1754-1763. The French were defeated. The Pontiac’s Rebellion of 1763’s defeat by the British of allied American Indian tribes, the lands south of the Ohio River became free of conflict. However, settlers homesteaded in this area in the early 1770s. The tribes were not happy with this and attempted to stop the settlement with various attacks.

In 1772, “Mad” Anthony Wayne’s first cousin, Levi Dungan, trekked from Philadelphia to Beaver County, settling on a 1000-acre land tract at the head of King’s Creek, which is now Ponderosa Golf Course. It was a disputed area as it lay on the Western frontier’s edge, where attacks from the indigenous were common. He made the area home, and it was known as Beaver County by 1800. He built a homestead of a large log cabin doubling as a blockhouse to protect from Native American raids. Later that year, he brought out his wife, the good doctor Mrs. Mary Davis Dungan, who had studied with the renowned Dr. Benjamin Rush, who was labeled as one of the fathers of American Medicine.

Mary began treating locals and helped homesteaders in the area. Legend has it that Mary hid her medical books in the crevasses of the springs to protect them from Indian pillaging, but a year later, upon her return, she discovered the books damaged from the weather and dampness. Most Native American attacks in the area took place at Levi Dungan’s settlement and Fort Dillow, 6 miles southeast of the site. There was a recorded attack near the spring where two men returning from a gristmill were attacked along Kings Creek. One man was killed, and the other, William Langfit, was seriously wounded. Langfit reached Dungan’s cabin, where Mary doctored him up. In addition to the Native American attacks, apparently, troubles with local wildlife were common – stories of a pack of wolves making a den in the ravine leading to the springs attacking a woman.

A homesteader named Isaac Stephens bought 400 acres around the springs for approximately $10 in 1778. He sold 12 of those acres for $300 to Edward McGinnis in 1827, who discovered the mineral waters and its ability to draw a profit. He reported that it healed his ailments. At the time, it was recorded that seven different springs flowing over the grotto – were pure and contained over 15 different minerals that possessed medicinal qualities.

McGinnis saw that the water was filtered naturally through the local geology and saw the business opportunity. It is unknown “who” discovered the healing properties or if they actually truly existed. It is believed the Native Americans in the area were aware of its curative powers, as a known tribal trail ran in close proximity to it. The healing powers were not just folklore in the area, as they were documented by medical experts prior to the resort’s opening. Dr. William Church of Pittsburg documented his study of the water in “The Philadelphia Journal of the Medical and Physical Sciences” in 1823 – where he explained visiting the springs and conducting 10 experiments. He discovered the spring had a wide variety of minerals, including carbonate magnesia (which acts as a laxative). He concluded the springs held mysterious healing properties. He stated, “Drinking the water, with the use of the cold shower bath, has been of great service to persons laboring under chronic rheumatism, gravel, dyspepsia, asthma caused by gastric irritation, general debility of the system, and convalescents from bilious fever, and liver complaints”.

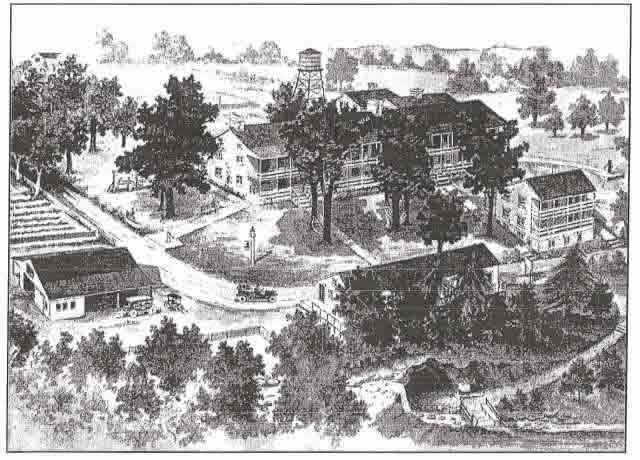

The resort was built in the mid-1800s by Edward McGinnis called “The Frankfort House”. It attracted visitors worldwide seeking to drink the magic waters that supposedly cured a variety of ailments from indigestion to kidney disorders. His resort could host over 200 guests every week of the summer. It became gentrified, sophisticated, and soon labeled an “elegant and exclusive” resort. The resort consisted of a three-story hotel with double-decker porches – the entrance to the rooms was from the porches as no interior hallways existed. The first floor had a dining hall, parlor, and ballroom. The back of the hotel contained the kitchen and pantries. The resort had an icehouse, a dance ballroom, and a 3 story guest cottage. Behind the hotel were vegetable gardens, ball fields, swings, and hammocks. The village built a hotel in town to handle the overflow of visitors to the resort, then came a post office, an academy school, a stagecoach stop, and churches along the Lincoln Highway. In 1873 McGinnis sold 80 of his acres to his kids.

By 1881 his daughters Eliza and Margaret sold the land to their uncle James Moore Bigger for $5,500. By 1882 a railroad was proposed to run from Shousetown (Glenwillard) to Frankfort Springs but never went through, even though some grading and prep work was initiated around where the Clinton exchange exists by Interstate 376 today. By 1884, Bigger completed a full-scale renovation. This included two dirt tennis courts and a dance hall, with a resident physician on staff named Franklin Kerr. The resort housed farmers who grew much of the food needed for the resort.

The resort saw a decline by the 1900s with the decline of the Victorian era. Numerous speculative owners and managers came and gone thinking they could revive it. To attract more visitors, the resort advertised more strategic advertising of the waters’ properties. They began bottling the water and selling it or letting visitors bottle it themselves. The hotel continued the business until 1912, then remained as only a restaurant and a stopping point for travelers. The then-resident manager 1914 advertised the use of the hotel for private parties and groups, with a special rate and a chicken/waffle dinner. From the 1920s to the 1930s, the restaurant still operated, but guests could no longer book rooms. By the 1920s, it was home to Route 18 Pennsylvania State Highway construction workers.

It was believed that a careless resident’s wood stove, befell tragedy as a devastating fire destroyed the resort in October 1932. No one was injured. The cause of the fire was never determined, but the resort was unsalvageable as it was the time of the Great Depression. The dance hall survived that first fire and was used as a social hall/venue for many more years. It was used for jazz bands and as a social hall from the 1930s to 1940s. It no longer exists.

Raccoon Creek State Park was established nearby in 1945, and by 1967, they had purchased the land and taken over the springs. It was stated that in 1972 the last remaining building – the guest cottage, was reduced to a one-story building housing a museum. This was broken into, and all the artifacts were lost.

Before the pandemic, Patrick Adams and Brady Wassom used to give guided tours by appointment through the visitor center or by calling 724-899-3611.

References:

- Adams, Patrick 2010 “Frankfort Mineral Springs” Raccoon Creek State Park Guide, Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources.

- Bausman, Joseph H. 1904 History of Beaver County, Pennsylvania, and its Centennial Celebration. New York: Knickerbocker Press.

- Cheney, Jim 2020 Pennsylvania Waterfalls: Frankfort Mineral Springs Falls in Raccoon Creek State Park. Uncovering PA website referenced 4/11/21. https://uncoveringpa.com/frankfort-mineral-springs-falls-raccoon-creek-state-park

- Church, William 1823 “An account of the Frankfort Mineral Springs” The Philadelphia Journey of the Medical and Physical Sciences, Volume VI. Philadelphia.

- Day, Sherman 1843 Historical Collections of the State of Pennsylvania. Philidelphia: George W. Gorton.

- Farm and Dairy 2003 “Defunct mineral resort has a healing history”. http://www.farmanddairy.com/news/defunct-mineral-resort-has-a-healing-history/6095.html

- Ryall, Kay 1933 “Frankfort Springs One of the First Settlements in Western Pennsylvania. Pittsburgh Press, 5 Nov 1933: 12.

- Schneider, Kevin 2009 “Take a Sip and Fix Your Hip”, PSU.EDU website referenced 4/11/21: http://pabook2.libraries.psu.edu/palitmap/FSprings.html

- Snedden, Jeffrey 2016 “Frankfort Springs mineral resort lost in time” The Times Online. website referenced 4/11/21 at timesonline.com/article/20160301/Opinion/303019980.